Many of the things we do, such as putting up a tree for Christmas or brides wearing white feel like habits that have always been with us. However, both of these traditions, along with many others, were popularised relatively recently in the nineteenth century. One fashion from this time that hasn’t stayed with us is the making of death masks.

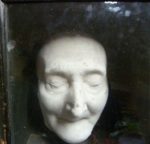

Death masks of some sort or another were made for millennia across the world, with the earliest evidence coming from Egypt. The Mycenaeans, Romans and Mayans also made death masks. A full body mould was made of Julius Caesar, which included detail of all his stab wounds. Over the centuries, many famous death masks were made, including those of Dante, Henry VII (left), Oliver Cromwell and Jonathan Swift. These were made by artists and sculptors who sought an accurate likeness to create a painting or effigy of notable figures. It was only in the nineteenth century that the masks began to be seen as valuable in their own right. Rather than just being the preserve of the nobility and famous, wealthy and upper middle class families started to have death masks made of loved ones. One of the families who decided to follow this Victorian trend lived in Rathfarnham Castle.

In 1852, the Loftus family left the Castle for the last time after nearly 300 years of on and off ownership since its construction in 1583. The new owners were the Blackburne family.

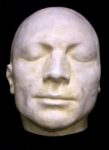

In 1852, the Loftus family left the Castle for the last time after nearly 300 years of on and off ownership since its construction in 1583. The new owners were the Blackburne family.  A member of the legal and administrative elite in Ireland, Lord Chancellor Francis Blackburne set about modernising the Castle. Over time a glasshouse was built, walls were removed, and toilets were installed, along with gas and possibly electric lighting. Many of these alterations were removed in the twentieth century. However, something that has stayed with us from that time is a death mask. It is most likely to be that of Georgina Arabella Blackburne (1837-1911), wife of Edward Blackburne (1823-1902). We have no information about where it was made or even who decided to have the mask made. Despite it being a very personal object, it appears to have been left at the Castle after Georgina’s grandchildren decided to sell the Castle and estate in 1912. The Jesuit Order as the new owners of the Castle kept the mask and it was still watching over the building when the OPW bought it in 1987. It is still in the Castle as part of the museum collection, but unfortunately visitors to the Castle will not see the death mask. Due to its delicacy it is not on display. Although we know very little about Georgina, she now has the unique honour of being the Castle’s longest known resident.

A member of the legal and administrative elite in Ireland, Lord Chancellor Francis Blackburne set about modernising the Castle. Over time a glasshouse was built, walls were removed, and toilets were installed, along with gas and possibly electric lighting. Many of these alterations were removed in the twentieth century. However, something that has stayed with us from that time is a death mask. It is most likely to be that of Georgina Arabella Blackburne (1837-1911), wife of Edward Blackburne (1823-1902). We have no information about where it was made or even who decided to have the mask made. Despite it being a very personal object, it appears to have been left at the Castle after Georgina’s grandchildren decided to sell the Castle and estate in 1912. The Jesuit Order as the new owners of the Castle kept the mask and it was still watching over the building when the OPW bought it in 1987. It is still in the Castle as part of the museum collection, but unfortunately visitors to the Castle will not see the death mask. Due to its delicacy it is not on display. Although we know very little about Georgina, she now has the unique honour of being the Castle’s longest known resident.

Today the decision to have a death mask made of a loved one seems to be odd or even morbid and gruesome. However, during the nineteenth century death and mourning became more and more performative and an opportunity to display one’s good standing in society. This is seen in the expense spent on funerals and how people dressed. In 1884, a man spent over £12 on his family plot in a Cork graveyard, which is approximately €7,000 today. This extreme example doesn’t even include the cost of the funeral and the undertakers. Your dress was another way to show your deference to the deceased. Queen Victoria made this even more popular when after the death of her husband Prince Albert she wore black mourning clothes for the rest of her life. Death masks were just another way that families could both remember their loved ones and demonstrate their knowledge of fashion and culture. Generally, great care was taken with the death masks, especially because of their fragility.

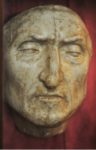

The process of making the masks was also very delicate. Death masks have to be made very soon after death, before the body is cold and stiff. The face and especially the hair are painted over with oil so that the plaster does not stick to them. The initial layer of the plaster captures all of the detail and subsequent ones are to hold it all together. A thread is placed vertically down the middle of the face and removed before the plaster sets to create a perforation to help remove the plaster. (This perforation can be seen clearly in some examples, for instance Dante’s, left) When this is done the two pieces are put back together and it is from this mould that the death mask is made. Death masks are typically made of plaster or wax, but some are made of bronze or even marble.

The process of making the masks was also very delicate. Death masks have to be made very soon after death, before the body is cold and stiff. The face and especially the hair are painted over with oil so that the plaster does not stick to them. The initial layer of the plaster captures all of the detail and subsequent ones are to hold it all together. A thread is placed vertically down the middle of the face and removed before the plaster sets to create a perforation to help remove the plaster. (This perforation can be seen clearly in some examples, for instance Dante’s, left) When this is done the two pieces are put back together and it is from this mould that the death mask is made. Death masks are typically made of plaster or wax, but some are made of bronze or even marble.

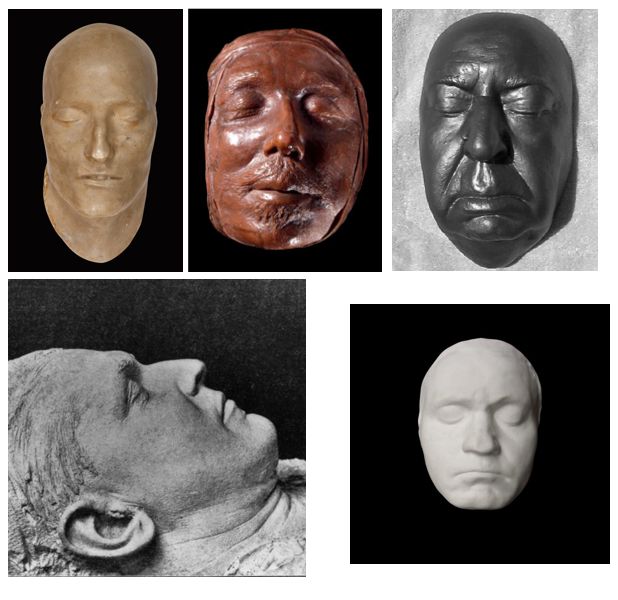

While death masks of loved ones became popular, they continued to be important tool for depicting the great and the good (and the not so good), especially in a time before photography. Probably the most famous manufacturer of death masks is Madame Tussaud (1761-1850). Before she established her world famous wax museum in London, Marie Tussaud (née Grosholtz), made waxworks in Paris and even ended up living in Versailles, working for Louis XVI. Up to this point her waxworks were modelled from life, but her work became much more gruesome with the start of the French Revolution. In order to protect herself from the charges of being a monarchist, Marie started to make death masks of those who had just been guillotined, including Robespierre (right, copy of Tussaud original).

Another reason for the large number of death masks from the nineteenth century was the development of Phrenology as a science. Phrenology was based on the idea that a person’s characteristics and mental ability could be determined by the measurements of a person’s skull and facial features. The skull was divided up into 27 different sections, each section relating to a different characteristic, such as combativeness or cautiousness. It was used extensively in research on criminal behaviour during the Victorian period, and also influenced the development of the studies of anthropology and evolution. A death mask from the infamous grave robber and murderer William Burke was made after his execution in 1829 to study his natural tendencies to criminal behaviour. Although completely discredited today, it garnered a strong following within certain groups in society. For instance, the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, Richard Whately stated ‘I am as certain that Phrenology is true as the sun is now in the sky’. Furthermore, Queen Victoria twice invited George Combe, the founder the Edinburgh Phrenological Society, to Buckingham Palace to ‘read’ the heads of her children. Even more strangely the British Phrenological Society continued in being until 1967.

It was used extensively in research on criminal behaviour during the Victorian period, and also influenced the development of the studies of anthropology and evolution. A death mask from the infamous grave robber and murderer William Burke was made after his execution in 1829 to study his natural tendencies to criminal behaviour. Although completely discredited today, it garnered a strong following within certain groups in society. For instance, the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, Richard Whately stated ‘I am as certain that Phrenology is true as the sun is now in the sky’. Furthermore, Queen Victoria twice invited George Combe, the founder the Edinburgh Phrenological Society, to Buckingham Palace to ‘read’ the heads of her children. Even more strangely the British Phrenological Society continued in being until 1967.

Death masks continued to be made in the first decades of the twentieth century. However, over time they reverted back to only being used by artists and sculptors.

If you want to have a look at some examples of death masks, Princeton University have digitised their collection, which is the largest in America: https://library.princeton.edu/special-collections/topics/death-masks The National Gallery also have number of examples, including that of Robert Emmet and George Bernard Shaw. The Medieval Museum in Waterford houses Ireland’s oldest death mask which is of the Franciscan friar and priest Luke Wadding (1588-1657). The mask was used to create his statue, which now stands outside the French Church in Waterford. (Random Fact: Luke Wadding was the one to advocate for St Patrick’s day to become a feast day.)

Test your ability to recognise these famous figures from history (Answers below)

uǝʌoɥʇǝǝq ‘suıןןoɔ ןǝɐɥɔıɯ (ɹ-ן ɯoʇʇoq) ʞɔoɔɥɔʇıɥ pǝɹɟןɐ ‘ןןǝʍɯoɹɔ ɹǝʌıןo ‘ǝʇɹɐdɐuoq uoǝןodɐu (ɹ-ן doʇ) :sɹǝʍsuɐ